All Your Bytes Are Belong to Us

2025-12-01 | By Nathan Jones

(An) Introduction (to hardware security)

Network security for internet-connected devices is a big deal (or so I hear). Anytime a device connects to the broader internet, people from all over the world are given the opportunity to probe and poke and potentially exploit that device. But network security is only half the battle! All electronic devices (even the ones that don't connect to the internet or have any wireless radios of any kind!) are susceptible to hardware attacks, which a threat can conduct if they have physical access to a device (or even, in some cases, if they don't, but that's an article for another day).

Think about it this way: if you're a security-savvy individual, you may be completely confident that an attacker, sitting in your driveway, could never access or infiltrate your home Wi-Fi network. That's excellent network security! But what if that same attacker could walk into your home and had full physical access to your router, able to take it apart, probe it, or modify its circuit as they pleased? How confident would you be in that scenario that your network could withstand that type of attack?

Hopefully, most of you are, perhaps, a bit more worried at that prospect, though many of you may be wondering, "Okay, but what could they even do with physical access to my router?" Such is the purview of hardware security, and that, my friends, is the very question I hope to (broadly) answer in this article. Hardware security is a very real and very important topic, and not just for internet-connected devices that an attacker might have physical access to, either, but for all electronic devices, like I mentioned just a little bit ago. The chip-enabled credit card in your wallet isn't internet-connected, but you'd sure as heck hope that the designers of that circuit have ensured that it's resistant to hardware attacks in the event that it ever physically fell into the wrong hands. Heck, even if your device just has a simple password-protected UART interface, it's still possible to conduct a timing or a fault-injection attack that could allow an attacker to easily gain access to your device.

Fair warning: If you've never thought about hardware security before, you may think before we're done that there's absolutely no stopping an attacker with physical access to your device and the world is ending, and, to paraphrase the infamous words from the 1991 video game, "Zero Wing", "All our bytes are belong to them".

But fear not! Just as with network security, every attack costs an attacker something: time, money, patience, etc. The goal is not necessarily to completely prevent an attacker from being able to exploit your device but to make it painful enough for them to conduct an attack that it's not worthwhile for them.

On that thought, we'll organize hardware attacks on a spectrum of how difficult/expensive/invasive they are to conduct. There are six levels on our spectrum of hardware attacks, from simply "researching a device" (not hard, not expensive, may not even require opening up the device) to "decapping the main IC and using crazy expensive lasers or scanning electron microscopes to attack the silicon itself" (very hard, very expensive, very intrusive!).

Let's get started!

Level 1: Researching

The first thing an attacker is going to do is research the device they want to attack. With good "Google Fu" skills and without even opening the case, they might be able to find the following data or information:

- Product manuals, detailing the correct operation of a device and what types of ports are open to a user

- Schematics and firmware, especially if a device is open-source (or if the device has already been reverse-engineered by another party)

- Encrypted firmware can be decrypted once the private key has been discovered using a side-channel attack (see Level 4)

- Firmware contents can also sometimes be guessed at by looking at popular library code or by searching for applicable appnotes. For instance, if an attacker knows that a device is using an ST microcontroller and has a bootloader, the attacker might surmise that the developer searched for "st bootloader appnote" and, if one such appnote exists, copied the example code.

- Datasheets for internal components

- Repair tutorials, depicting a device's internal components and PCBs

- Patent filings

- FCC filings, which can include internal photos and information about the device's operation

Opening up the case (and probing around with a continuity tester or conducting a boundary scan with JTAG) can reveal other key information, such as:

- The exact ICs used (for the main controller, external flash, etc.)

- The full schematic (after you've reverse-engineered it)

- Unlabeled JTAG/programming/UART ports (which will be particularly useful in the next step)

This type of freely available information is more than harmless. As noted in The Hardware Hacking Handbook, information gleaned from publicly available patent filings allowed security researchers to defeat both the Cisco root of trust and the main security mechanism in x86 CPUs. The US Army even recognizes OSINT ("open source intelligence") as one of its seven main intelligence disciplines!

Level 2: Snooping

Armed with all of this information, the next thing an attacker might do is use a logic analyzer or protocol adapter to probe the device as its operating.

At first, this activity may simply be passive, but much can be learned by listening to the signals being sent back and forth between ICs inside the device.

- Is an unencrypted firmware being loaded from external memory upon device startup?

- What signals does the main MCU send to external sensors or actuators to control them?

- How much time transpires between a login attempt and an "Access denied" response?

Even if this information does not compromise a device on its own, it could be used later to conduct a more sophisticated attack on the device.

- A password-protected UART shell may be susceptible to a timing attack, a form of side-channel attack (see Level 4).

- Corrupting a transmission between the main MCU and a peripheral (via a clock or voltage glitch, for example, see Level 5) may put the device into a vulnerable state.

- The PlayStation 3 was hacked in 2010 in exactly this manner, by glitching a memory operation between the MCU and external memory that resulted in a memory leak. This memory leak could then be exploited to allow a user to eventually control the hypervisor on the PS3.

In a more active form of "snooping", an attacker may look for an unlabeled JTAG/programming or serial port to control or inject signals into.

- An unlocked JTAG port could allow an attacker full control over an MCU

- A locked JTAG port could still be susceptible to a fault injection attack that overrides/bypasses the protection mechanism!

- A serial port (intended for developer or repair access to a device) might have a default login (which is easily guessed)

- A USB port on a device running a major OS such as Windows could allow an attacker to attach a keyboard and press CTRL+ALT+DELETE, gaining full control over the device (there wouldn't even need to be a physical USB port on the device if an attacker could solder one on to a set of known USB pins!)

(I heard about the last two vulnerabilities above on episode 339 of the Embedded.fm podcast ["Integrity of the Curling Club"], in which they were listed as being known deficiencies in production electronic voting machines!)

Level 3: PCB modifications

At this level, an attacker may begin physically modifying a device in order to conduct their attack.

For instance, a device may use pull-up, pull-down, or 0-ohm resistors for various configuration settings. Removing or changing these resistors may allow an attacker to put a device into an unintended state that allows for unauthorized access or for a later attack.

An external memory IC can be desoldered and read out or loaded with attacker-controlled code.

Additionally, conducting a side-channel or fault-injection attack (see Levels 4 and 5) may require an attacker to modify a PCB by adding shunt resistors, removing power filtering capacitors, or cutting certain traces to allow an attacker to control an MCU's clock or voltage.

Level 4: Side-channel attacks

All electronic devices, it turns out, have side effects while they're running. They're not just encrypting a message; they're also drawing power and generating heat. They're executing an encryption over a very specific length of time. They're generating error messages to specific incorrect inputs. Each of these qualities (power consumption, heat, execution time, and faulty outputs, respectively) represents a way in which an electronic device "leaks" information about what it's doing, and each of these things tells us a little bit about what's going on inside that electronic device. This leaked information is called a "side-channel" and using it to infer what a device is doing is called a "side-channel attack".

Zhou, Yongbin & Feng, DengGuo. (2005). Side-Channel Attacks: Ten Years After Its Publication and the Impacts on Cryptographic Module Security Testing.. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2005. 388. https://eprint.iacr.org/2005/388.pdf

Zhou, Yongbin & Feng, DengGuo. (2005). Side-Channel Attacks: Ten Years After Its Publication and the Impacts on Cryptographic Module Security Testing.. IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2005. 388. https://eprint.iacr.org/2005/388.pdf

Have you ever forgotten a website login, been told "You've entered an incorrect password", and thought to yourself, "Aha! My username, at least, must be correct." If so, you've successfully conducted a small side-channel attack on that website by leveraging the fact that the faulty output ("You've entered an incorrect password") leaked information that your username was (likely) correct; otherwise, the website would have flagged the username as being incorrect first.

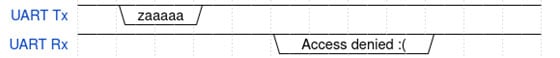

Another example of a side-channel attack, this one exploiting a microcontroller's execution time, can be used to compromise a password-protected login.

>> Enter password:

Once a password has been entered, many devices will perform a byte-by-byte comparison to the correct password using something like strcmp.

char * correctPw = "123456";

if(strcmp(enteredPw, correctPw) == 0) printf("Access granted! :) \n");

else printf("Access denied :( \n");

The problem is that a function like strcmp will return -1, 0, or 1 as soon as it knows its return value. If we enter "hello" at the prompt, strcmp will return immediately after checking the first character. If we enter "123checkcheck123", then strcmp won't return until after the first four characters have been checked. If we were to time how long it took that device to print "Access denied :(" to the terminal, we could figure out how many of our characters were guessed correctly!

In the last trace above, the MCU took just a liiittle bit longer to send the "Access denied :(" message, which we can surmise was because the first character of that password attempt was correct.

If we assume that passwords on this device are limited to just lower-case letters and numbers, we'd only need to try, at most, 36 different passwords to determine the first character of the device's password. The first time strcmp takes a little longer than normal to return, we know we have our first correct character. Then we'd simply wash, rinse, and repeat to figure out the rest of the password. Rather than needing to randomly guess at 366 possible passwords, we'd only need to guess at most 36 * 6 passwords!

The Vantec NexStar Vault HDD (model #NST-V290S2), which was sold as recently as the mid-2000s, was susceptible to exactly this type of attack. Although the device was protected by a 6-digit pin, the firmware checked each entered pin in this byte-for-byte fashion, signaling the error LED as soon as it knew the pin was incorrect. Connecting a logic analyzer to the error LED on the inside of the enclosure would reveal how long the firmware was taking to check the pin number that was entered, thus enabling the attack.

Famously, side-channel attacks that target a device's power consumption can even be used to determine the private cryptographic keys being used by that device for encryption and decryption!

This happens because there is a direct and linear correlation between how much power a device draws and how many transistors are on inside that device; determining which bits of a private key are "on" versus "off" simply becomes a matter of gathering sufficient data and then analyzing it correctly. A "differential power analysis" (DPA) attack on AES128, for instance, begins by having the device encrypt a few thousand different blocks of plaintext.

Then, a guess is made at the value of the lowest byte in the private key (key[0]). For each of the lowest bytes in the blocks of plaintext that were encrypted, we use this key guess to calculate one of the intermediary values during the first round of AES encryption. The power traces we recorded are then sorted into two groups based on whether the lowest bit of that calculated result is a 0 or a 1, and the two groups are averaged and subtracted from each other. If our key guess was incorrect, then we essentially just sorted the power traces randomly, and the result of their subtraction will be a trace that's mostly zero. However, if we did correctly guess key[0], then there will be an ever-so-slight difference between our two sets of traces, owing to the fact that bit 0 truly was a 1 during some of those encryptions, and we can see the effect of that one transistor in the power trace! (For a more detailed explanation of a DPA attack on AES128, see here.)

In this manner, we only need to make 4,096 guesses at the private AES key (256 possible key values for each of 16 key bytes), as opposed to making 2128 guesses!

Here's a video of me performing the analysis step of this attack, using a set of tutorials provided by NewAE Tech. You can fast forward to the end after watching the first 30 seconds or so (my computer was being really slow that day); the last two lines that are printed are the guess I was able to make at the AES key, followed by the actual AES key. (Yay! They match!) The only data being operated on by this code are the power traces (which I recorded just prior to this video); nothing else!

Level 5: Fault injection attacks

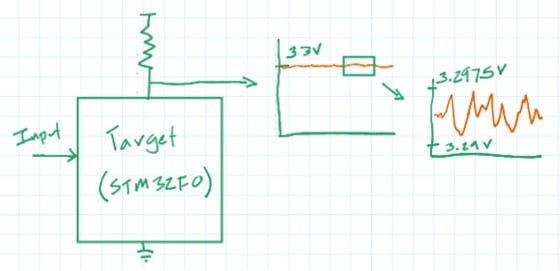

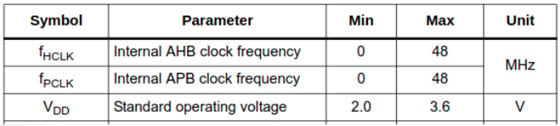

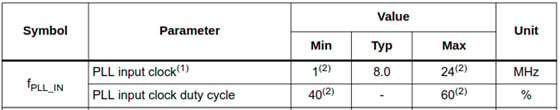

As designers of electronic devices, we are intimately familiar with the idea that the components we use have specific operating conditions that must be met, or our device won't function. Voltages must be within certain ranges, temperatures must not exceed or fall below certain values, clocks must have certain frequencies and duty cycles, etc. The following tables, for instance, show a few of the operating requirements for an STM32F0 microcontroller.

Actually, it's not quite correct to say that "the device won't function" if these operating conditions aren't met, just that "we can't guarantee what the device will do", and it's in this ambiguous space where fault injections live.

Running the STM32 above at 0.1V certainly won't work, but what if that lasted for less than a single clock cycle? What if we sent in a 96 MHz clock to the PLL (well above the 24 MHz upper limit), but only for a single cycle?

Sometimes, the device truly won't work; it will go into reset or trigger a Hard Fault or something. Sometimes, though, these faults may do something really interesting, such as:

- Skip over the current instruction

- Alter the current instruction

- Alter a value in RAM or in one of the CPU registers

For many attacks, exactly which of these faults occurs is not actually important, only that the device malfunctions during a critical operation.

The LPC family of microcontrollers from NXP, for instance, has a "code read protection" (CRP) feature that prevents anyone from reading out internal memory if a register ("CRP") is set to a specific value.

The CRP register allows for four different levels of code-read protection (see above). Importantly, these modes are enabled by setting the CRP register to one of four specific values; code-read protection is completely disabled if any other value is found in the CRP register during start-up. In 2017, Chris Gerlinsky demonstrated at REcon Brussels that a fault injected right when the CRP was being read could cause the LPC microcontroller to read an invalid value (actually, there are a few different places during MCU start-up where a glitch could potentially bypass the code-read protection). If this value was anything other than one of the four values that enabled code-read protection, the device would assume code-read protection had been disabled, giving a person full control over the microcontroller. (Whether this occurs by corrupting the memory load instruction or by corrupting the actual data value is immaterial to the success of the attack.)

In other fault injection attacks, a glitch could have the result of flipping a Boolean value from true to false or of forcing the target to take a conditional branch it wasn't supposed to take. In fact, this is exactly how hardware hackers were able to run their own code on the Xbox 360 in 2011. The Xbox 360, before loading and running its kernel, checked that the kernel's SHA matched an expected value, which was intended to prevent unauthorized code execution. Furthermore, this check essentially boiled down to a single memcmp function call.

// Overly simplified Xbox code if(memcmp(kernel_sha, exp_sha) == 0) run_kernel(); else error();

If the reset pin on the CPU was pulsed at juuust the right spot (right around the time when memcmp was returning), it was possible to force the return value to be 0 (meaning the two pieces of memory, the two SHA values, were identical) without fully resetting the device; the CPU would continue executing the rest of its startup code. In this manner, a non-verified kernel could be loaded in the Xbox's NAND Flash and then run, despite not having a valid SHA.

Glitching the voltage, clock, or reset line on a device are a few ways to conduct a fault injection attack, but there are others.

In an electromagnetic fault injection, a strong magnetic field is momentarily created over top of the target to induce faults using a powerful electromagnet. Interestingly, this now allows an attacker to position their means of attack (the electromagnet) in a 2D plane over the target, potentially allowing them a much greater ability to target specific parts of the microcontroller (such as the ALU, the registers, the instruction register, etc.).

(Optical or laser fault injections are another interesting one; I'll mention those in the next section!)

Fault injection attacks are conceptually easier than many side-channel attacks, but they require a lot of guessing and checking on the part of the attacker (read: they can take much longer without any indication of even partial success), and they have the chance of permanently damaging the target, which makes them an overall more difficult/intrusive attack than a side-channel attack.

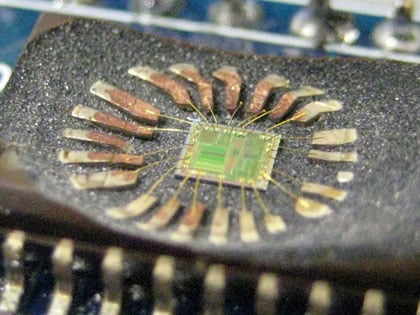

Level 6: IC decapping

At the end of the hardware hacking spectrum are the most expensive, difficult, and invasive attacks that we've looked at thus far, all facilitated by first carefully decapping the IC that we wish to attack, exposing the internal silicon that makes the IC what it is.

Decapping an IC typically requires very strong chemicals or lasers and may require rebonding the pads to the die afterward. (Other methods exist, but most have a high chance of destroying the IC to some extent, which is less useful for a hardware attacker.)

Owing to the fun interactions between electrons and photons, an exposed silicon die opens up new, optical-based attacks to an attacker. For instance, switching transistors will occasionally emit a photon, and this allows an attacker to conduct a side-channel attack by measuring this photonic emission with the appropriate sensor. Inversely, an attacker can use a laser to conduct optical fault injection. Like EMFI, optical fault injection attacks have a spatial locality that permits targeting specific parts of the IC being attacked.

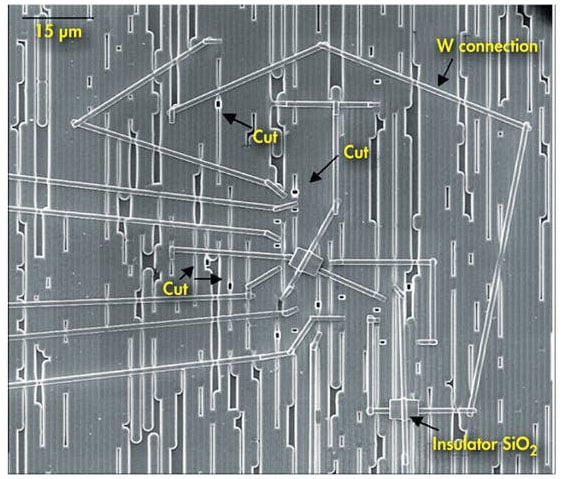

Exposed dies aren't just susceptible to optical attacks; they can be actively changed using a technique called "focused ion beam (FIB) editing". Using FIB editing, silicon on the die can be cut or deposited, changing the very nature of how the IC operates.

Accessing deeper layers of the IC is difficult with this technique, but not impossible. With FIB editing, an attacker can very nearly create their own IC out of the parts you give them in your device.

Conclusion

Any internet-connected electronic device needs security mechanisms to prevent bad actors from finding it on the internet and causing havoc with it. In the same way, any electronic device that individuals have physical access to (i.e., all of them!) needs hardware security to prevent the same bad actors from the same malicious activities.

These hardware attacks can range in cost, difficulty, and effectiveness from researching and reverse engineering the device (cheap, easy, only somewhat effective) to decapping the IC and altering its very silicon with FIB editing (expensive, difficult, and highly effective). Side-channel and fault-injection attacks lie in the middle and are easy enough to execute that many devices today likely need to consider implementing countermeasures against them.

So, are we all doomed? No! Not only do countermeasures exist for all the attacks discussed in this article (which is a topic for another day!), but a device's hardware security only needs to be "good enough" to thwart whichever attackers are trying to get whatever secrets are on your device. Relatively very few people have access to a FIB editor (much less the expertise to operate it), which means most devices simply don't need to worry about that type of attack.

What attacks you do need to worry about depend on what you're protecting and who you're protecting it from. Only you can answer that question, and, hopefully, you know enough now to begin answering that question.

Resources and going further

Much of the material in this article was developed by reading The Hardware Hacking Handbook. I highly recommend it!

You can hear the authors of that book on the Embedded.fm podcast in the following episodes:

- Ep. 286: "Twenty Cans of Gas" (Colin O'Flynn)

- Ep. 431: "Becoming More of a Smurf" (Jasper van Woudenberg)